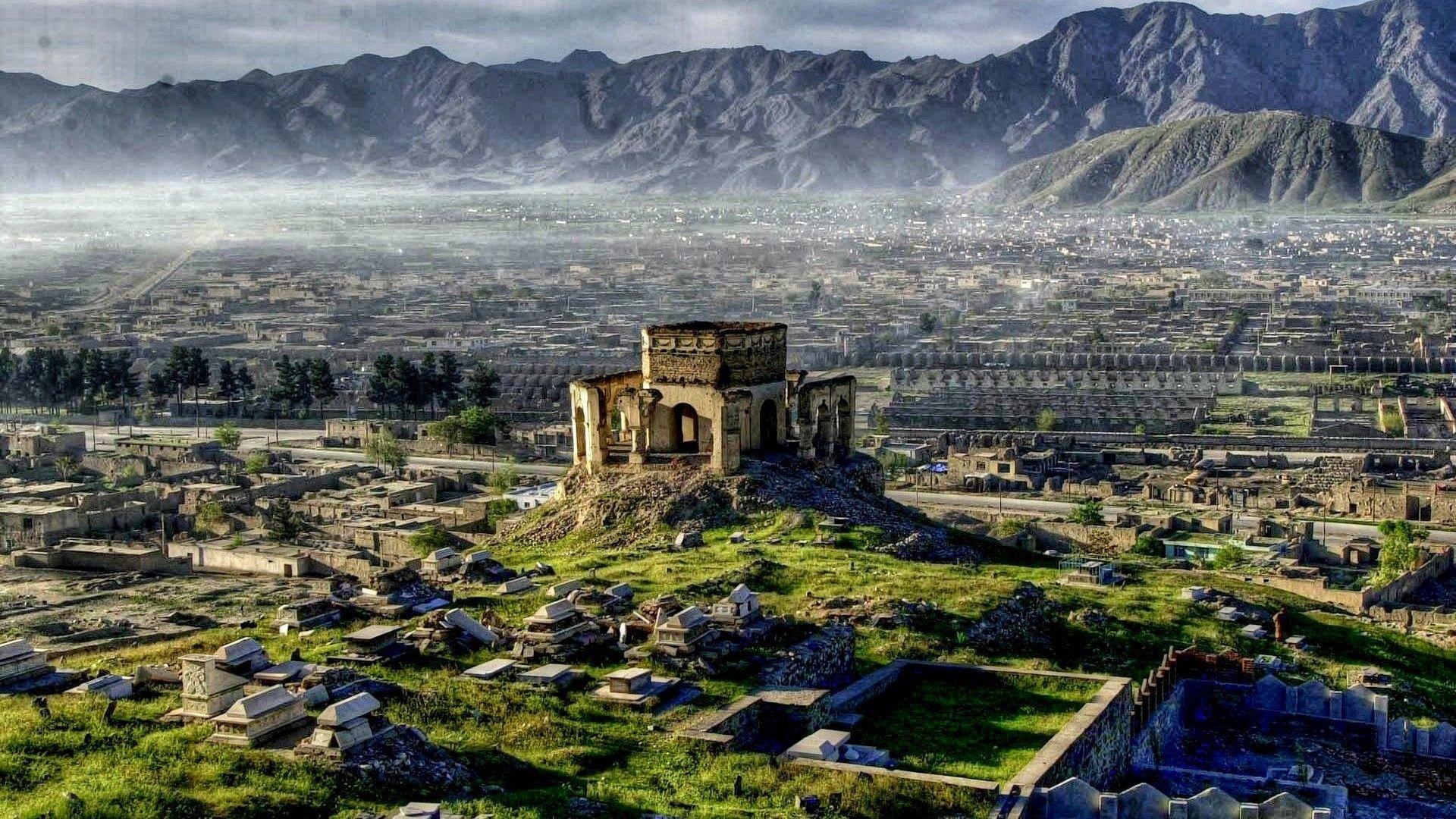

How Afghan Economy Should Prepare to Weather the Coronavirus Pandemic

On 30th January 2020, the World Health Organization declared the Coronavirus a Public Health Emergency of International Concern or Pandemic. By end of April 2020, the confirmed cases for the Coronavirus passed 3 millions globally. While being a public health crisis, the Coronavirus outbreak has caused national economies to shrink. Particularly, its impact is most felt in the disruption of global supply chains. A supply chain is a collection of organizations (e.g. producers, suppliers, wholesalers, logistic service providers, etc.) that work together across national borders to provide a product or service to a customer. Think about this scenario: You go to Kabul City Center to buy an iPhone, which is assembled in the U.S. with spare parts that were shipped from Chinese suppliers. When countries impose quarantine measures to limit the spread of the new virus, supply chains suffer from bottlenecks. The main reason is that factories have to halt or significantly reduce their production, so raw materials become scarce; also, border closures restrict transportation of goods, so market supply faces shortage or extended delays to fulfill demands.

As I argued in this earlier op-ed here, Afghanistan must take steps to hedge against the risk of supply-chain disruptions. The Afghan economy has two major weaknesses. First, with a large negative trade balance, Afghanistan has a trade deficit that makes it heavily dependent on import from abroad. Second, the incremental economic growth that is driven mainly by a strong agriculture in 2019 requires Afghans to increase their export of agricultural products overseas. Given that the pandemic is pushing the countries across the region to limit the movement of people and goods, Afghanistan is likely to face challenges in procuring and transporting materials for import and export purposes.

Why should you care about supply chains?

Supply chain disruption means that Afghans would struggle to find reasonably priced essential household supplies in their local markets. Media already reports that Afghan hospitals face a large shortage of personal protective equipment, testing kits, and ventilators, which increasingly jeopardize the fight against Covid-19. Therefore, every Afghan businessperson should be concerned about two issues: Is my company prepared to deal with supply chain disruption? How risk-vulnerable is my company in its supply chain? Without preparedness to tackle supply chain disruption problems, it will be difficult for the Afghan economy as a whole to weather the pandemic.

How should you minimize supply chain disruption?

It is not possible to reliably estimate which sectors will be affected the most in Afghanistan without empirical data. But, the realistic expectation would be that health and food sectors are likely to face delivery delays and spikes in price levels. One reason may be that products in these two sectors are largely imported from countries that are now under lockdown. To avoid going down this path, the Afghan government and the private sector must enter into a cooperative mechanism in the form of a public and private partnership. Here are a few steps that must be implemented:

First, relevant government institutions at national and provincial level need to work together with the chamber of commerce to identify the list of at-risk products (i.e., products that become unavailable in the bazaar or just too expensive). This will help businesses to plan ahead and find alternative sources of supplies for these products before the market faces a critical shortage. Preparing such a list also creates a more solid understanding in society about priority goods and services during the pandemic.

Second, most Afghan businesses may not have the expertise or resources to broaden their supplier base or know how much raw materials to procure and store. Therefore, the government must create a dedicated logistics task-force to mobilize its vast resources in support of the private sector’s supply chain. This government-sponsored logistics task-force should provide Afghan businesses with physical, informational and bureaucratic support. For example, Afghan embassies should host a sourcing unit that reports to this logistics task-force. This unit would be responsible to advise Afghan businesses, which import supplies from oversees, on getting information on the location and status of various suppliers or producers in the host country. It is important to at least locate tier 1 suppliers, come up with a plan for potential channel shifts, and find alternative logistics solutions. Moreover, Afghan businesses should expect increasing customs delays, change in customs procedures, and additional requirements on item specifications. Embassies can play a constructive role to expedite these bureaucratic problems, which otherwise would slow down the entire supply chain.

Third, the Afghan government must invest in building shared depots and warehouses in major cities and towns for the predefined priority goods. There is already some governmental prepositioning infrastructure for wheat, but that is not enough. Small and medium-sized businesses should be given access to warehousing space without rental fees or any other additional costs.

The bottom line is that the Afghan government must take on an enabling role to complement the supply chain capabilities of the private sector.

Author: Mujtaba Saleem

- 2020 May - 16